A Short History

While Chicago has long been known for music and for first-rate cultural institutions like the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Art Institute of Chicago, the city’s artistic production is easily underrated. The South Side has been home to many of the last century’s important artists, some of whom wrote about its streets long after leaving for other cities or countries.

From its founding to the end of the 19th century, Chicago was widely considered a cultural backwater, and not without cause. The great figures of the original “American Renaissance” of the middle 19th century resided chiefly between New York and Boston. Chicago became known for, if anything, a gritty and vivid style of newspaper journalism. The first quintessentially “Chicago” novels were about the squalor of the South Side’s ethnic working-class and vice districts: Sister Carrie (1900) and The Jungle (1906) by Theodore Dreiser and Upton Sinclair respectively. Though only Dreiser actually lived in Chicago for a significant period, both used their experiences of the city to craft landmarks of American social realism.

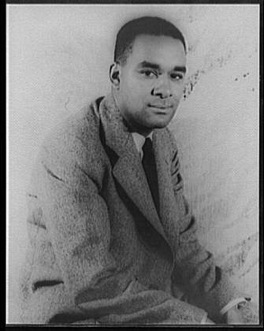

The first major American author to hail from the South Side was James T. Farrell (1904-1979), the son of an Irish family that lived on the blocks west of Washington Park. He attended the University of Chicago and later left the city, but his writings largely returned to the social world of Chicago’s South Side. He is most famous for his Studs Lonigan trilogy (1932-35) which recounted the short life of a lost young man from the South Side slums. A rough contemporary of Farrell’s, Richard Wright (1908-1960) spent several formative years living and working on the South Side. His most famous novel, the seminal Native Son, is set in and around Hyde Park and Kenwood. He also wrote the important introduction to the second edition of Black Metropolis (1945), Horace Cayton and St. Clair Drake’s groundbreaking sociological study of the “Black Belt.” Langston Hughes (1902-1967), another pioneer of African American literature, also lived and worked on the South Side before he moved to New York and his writing career brought him to national fame. While in Chicago, Hughes wrote for the Chicago Defender, one of the nation’s oldest and most prominent African American newspapers. Since 1905, the Defender has covered local and national news in and for the city’s African American community, and it has served as an important hub of Chicago’s black literary culture.

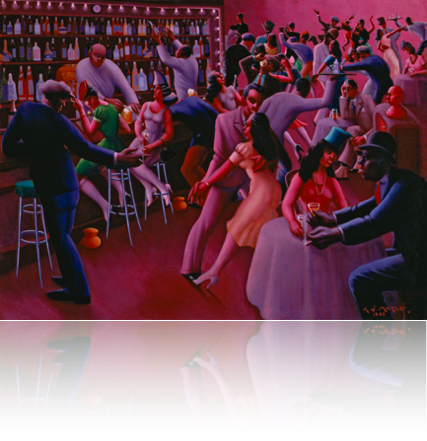

Florence Price (1888-1953) moved from Arkansas to the South Side and became one of America’s most prominent African American classical composers. Her work was the first by a black composer to be premiered by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. She integrated African American folk themes into classical European styles. Archibald Motley, Jr. (1891-1981) was, like Price and Wright, a native of the South who came to Chicago. He studied painting at the School of the Art Institute and in Paris and brought his training to bear in depicting the South Side nightlife. His famous paintings include “Bronzeville by Night” and “Blues.” Started by a Work’s Progress Administration project in 1940, the South Side Community Arts Center became a major part of Chicago’s black arts scene. Housing in a historic mansion at 38th and Michigan, the Center continues to host major shows and events. Margaret Burroughs, one of the key figures in the Arts Center, went on the found the DuSable Museum of African American History in Washington Park with her husband. The DuSable continues to be an invaluable resource for learning about African American history and culture.

The decades immediately following the Second World War saw the emergence of Chicago’s most famous writers. Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000) moved to Chicago as an infant and never moved away, penning volumes of poetry, a novel, and memoirs. She gave Chicago’s South Side its most sustained poetic treatment in books like Annie Allen (1949, the first work by an African American to win the Pulitzer Prize), Maud Martha (1953), and In the Mecca (1968). Saul Bellow (1915-2005), a native of Montreal, spent most of his life in Chicago, much of it teaching at the University of Chicago. The city in general and the University and the South Side in particular are the settings for The Adventures of Augie March (1953), Herzog (1964), and Humboldt’s Gift (1975), among many others. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1976 and moved to Boston in 1993 after teaching for many years on the Committee on Social Thought. Lorraine Hansberry (1930-1965), daughter of the plaintiff whose lawsuit overturned racial restrictive covenants in Chicago, wrote Raisin in the Sun (1959) as a fictional dramatic interpretation of the experience of trying to move into a white Chicago neighborhood. It was the first play by a black woman to be produced on Broadway.

In the 1960’s, New York’s Black Arts Movement came to Chicago. Allied with the Black Power movement, the Black Arts Movement stressed ethnic pride, solidarity, and independence from white artists, patrons, and aesthetic norms. Third World Press, still located in Woodlawn, is one of the institutions that nurtured the movement; when Gwendolyn Brooks left her major publisher, she went to Third World. The Organization of Black American Culture promoted Afro-centric arts, notably the “Wall of Respect” mural (no longer extant) in the neighborhood just north of Washington Park. Oscar Brown Jr. (1926-2005), a singer and playwright, cast youth gang members in some of his productions. The heady mix of politics, music, art, and theatre bubbled to the surface in community events like “Jazz n’ the Alley,” an informal music and arts festival that ran for decades and has recently been revived.

The legacy of the Black Arts Movement is preserved in organizations like the Association for the Advancement of Creative Music, in numerous spoken-word poetry events around the South Side, and in local art galleries. Likewise, the tradition of realism in Chicago literature pioneered by Farrell and made famous by Bellow has survived, with modifications, in the writing of South Side native Stuart Dybek (The Coast of Chicago, 1990). Neighborhoods once known for slums, slaughterhouses, and factories are now major destinations in the city’s artistic life. Pilsen and Bridgeport have both seen a rapid influx of artists and galleries, and something similar may be starting around 47th and King Drive. The population collapse that struck the South Side between 1960 and the late 1990’s seems to be reversing, and with it the area’s and the city’s presence in the nation’s culture.

Further Reading:

Saul Bellow, The Adventures of Augie March (New York: Viking Press, 1953)

--------. Herzog (New York: Viking Press, 1964).

--------. Ravelstein (New York: Viking, 2000).

Edgar M. Branch,. James T. Farrell (New York: Twain Publishers, 1971)

Gwendolyn Brooks, Annie Allen (New York: Harper, 1949)

--------. Maud Martha: a Novel (New York: Harper, 1953)

--------. The Bean Eaters (New York: Harper, 1960)

--------. In the Mecca: Poems (New York: Harper and Row, 1968)

James T. Farrell, Chicago Stories, Charles Fanning, ed. (Urbana, Ill: University of Illinois Press, 1998)

Lorraine Hansberry, A Raisin in the Sun: A Drama in Three Acts (New York: Random House, 1959)

George E. Kent, A Life of Gwendolyn Brooks (Lexington, Ky: The University Press of Kentucky, 1990)

Robert K. Landers, An Honest Writer: The Life and Times of James T. Farrell (San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2004)

Stephen Longstreet, Chicago, 1860-1919 (New York: D. McKay, 1973)

Howard Nemiroff, To Be Young, Gifted, and Black: Lorraine Hansberry in Her Own Words (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1969)

Richard Wright, Native Son (New York and London: Harper, 1940)

Arts & Literature

Learn More

uchicago®  ©2007 The University of Chicago®

©2007 The University of Chicago®  5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637

5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637  773-702-1234

773-702-1234

©2007 The University of Chicago®

©2007 The University of Chicago®  5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637

5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637  773-702-1234

773-702-1234

Image sources

Archibald John Motley, Jr., American, 1891-1981, Nightlife, 1943, oil on canvas, 91.4 x 121.3 cm, Restricted gift of Mr. and Mrs. Marshall Field, Jack and Sandra Guthman, Ben W. Heineman, Ruth Horwich, Lewis and Susan Manilow, Beatrice C. Mayer, Charles A. Meyer, John D. Nichols, Mr. and Mrs. E.B. Smith, Jr.; James W. Alsdorf Memorial Fund; Goodman Endowment, 1992.89, The Art Institute of Chicago. Photography © The Art Institute of Chicago.

Image not for download.

Richard Wright: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection, LC-USZ62-42502 (b&w film copy neg.)