Housing

Learn More

A Short History

Built on the flat, prairie shores of Lake Michigan, Chicago has expanded mostly unchecked by the sort of natural terrain features that hem in many American cities. Even the lakeshore has been filled in over time. The result is an urban geography shaped less by nature than by man—a landscape sculpted, at least in part, by a series of historical (and ongoing) struggles for space and territory among Chicago’s diverse citizens.

Chicago neighborhoods have often been identified by their ethnic composition. In the city’s early history, recent immigrant groups and longer-settled ethnic communities scrambled for space. University of Chicago sociologists studying the city in the 1920s divided Chicago into seventy-five community areas, most of which roughly approximated social borders dividing the city. Inspired by the often-tense rivalries these scholars observed in the city around them, they theorized that competition between groups for scarce urban resources—mostly land—drove urban development in a predictable, natural manner. Although the borders were increasingly fuzzy and rule-breaking exceptions were common, Chicago’s ethnic quilt was more or less stable by the turn of the century: Germans lived on the North Side, Irish on the South and Northwest Sides, Jews on the West Side and in Hyde Park, Bohemians and Poles on the Near Southwest Side and Near Northwest Side and a very small number of blacks in the South Side Black Belt. Despite this ethnic segmentation, scholars postulated that eventual assimilation would eventually result.

But observing the situation in 1945, University of Chicago-trained sociologists St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton noted that assimilation had been less likely for the city’s black community. While most ethnic enclaves tended to eventually break up, Drake and Cayton argued that “with the passage of the time the Negro are becomes increasingly more concentrated.”

The Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North strained Chicago’s urban fabric in new ways. Attracted by the promise of more equitable political rights, the possibility of earning an industrial wage and the excitement of urban life, black Southerners came north in droves. The Great Migration eventually brought over half a million blacks to Chicago.

Initially, the combination of sporadic anti-integration violence and the legal mechanism of racial restrictive covenants confined black Chicagoans to a small and increasingly overcrowded strip on the Near South Side known as the Black Belt. Although blacks contested the borders of their segregated community, territorial gains were incremental and orderly expansion, let alone integration, was constrained by the racial assumptions of surrounding communities, political leaders and financial institutions—including the University of Chicago, which funded the legal defense of restrictive covenants. Finally in 1948, with the Black Belt straining under unprecedented demographic pressure, the Supreme Court in Shelley v. Kraemer declared the enforcement of racial restrictive covenants unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Even with restrictive covenants gone, however, white Chicagoans used a variety of extra-legal mechanisms to restrain the expansion of black settlement. Most dramatically, white residents of integrating communities sometimes used violence to intimidate new black neighbors bold enough to break the residential color line. Meanwhile, powerful institutions and politicians looking to placate their white constituents used state and federal funds and the machinery of public policy to maintain a segregated Chicago. Most simply, many white Chicagoans spoke with their feet, leaving their increasingly black neighborhoods and moving to the city’s outskirts and surrounding suburbs.

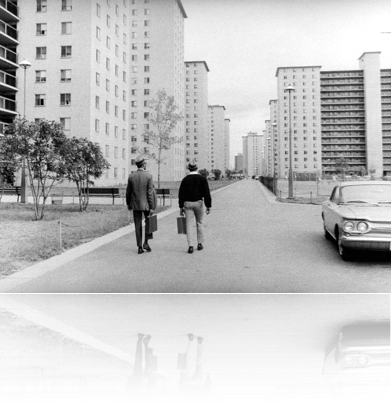

At an institutional level, urban renewal programs—pioneered by the University of Chicago in Hyde park—capitalized on the expansive eminent domain powers contained in a set of bills passed first by the Illinois legislature and later by the federal government in the 1940s and 1950s, to slow the pace of neighborhood change. Such efforts displaced many new black residents and raised the socioeconomic profile of certain neighborhoods even as they foisted the costs of renewal onto other, less politically connected communities. Meanwhile, large public works projects—especially the strategic placement of highways and enormous, multi-story public housing developments—hardened racial borders and constrained residential opportunities for many black Chicagoans.

Beginning in the 1960s, activists attempted to expose and contest the inequities of life in Chicago—with notable, if limited, success. In the summer 1966, Martin Luther King led supporters in a series of open-housing marches through hostile, exclusively white communities on the city’s Southwest Side and Northwest Sides, eventually securing a vague and ultimately meaningless promise from city leaders to promote open-housing efforts. In the same year, public housing residents charged that projects built in exclusively black neighborhoods perpetuated segregation. The case, Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, resulted in a federal judicial order to build new public housing units in non-black neighborhoods.

Today, the legacies of racial segregation still plague Chicago. Though formal and informal barriers have seemingly disappeared, blacks have become more concentrated in all-black communities and some communities remain mostly, though not exclusively, white—even as young and professional neighborhoods have integrated. The Chicago Housing Authority’s ambitious Plan for Transformation, approved in 2000, led to the demolition of large, segregated public housing projects and proposed to replace them with scatter-site, mixed-income developments. But with the Plan already behind schedule, housing activists remain skeptical of its eventual success. Meanwhile, renewed interest in urban life among professionals of all races has brought significant development to many of Chicago’s neighborhoods. Whether this development—and the elevation of land values and rents it brings with it—will improve the quality of life for neighborhood residents or displace (“gentrify”) poor communities remains an open question.

Further Reading:

Danielle S. Allen, Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004)

St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co, 1945)

Encyclopedia of Chicago, James Grossman, Ann Durkin Keating and Janice L. Reiff, eds. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004)

James R. Grossman, Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989)

Arnold R. Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago, 1940-1960 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983)

Nicholas Lemann, Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1991)

Alexander Polikoff, Waiting for Gautreaux: A Story of Segregation, Housing, and the Black Ghetto (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2006)

Peter H. Rossi and Robert A. Dentler, Politics of Urban Renewal: The Chicago Findings (New York: Free Press of Glencoe, 1961)

Amanda L. Seligman, Block by Block: Neighborhoods and Public Policy on Chicago’s West Side (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005)

Sudhir Alladi Venkatesh, American Project: The Rise and Fall of a Modern Ghetto (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000)

Clement E. Vose, Caucasians Only: The Supreme Court, the NAACP, and the Restrictive Covenant Cases (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1959)

uchicago®  ©2007 The University of Chicago®

©2007 The University of Chicago®  5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637

5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637  773-702-1234

773-702-1234

©2007 The University of Chicago®

©2007 The University of Chicago®  5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637

5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637  773-702-1234

773-702-1234 Image sources:

Robert Taylor Homes: Archival Photofiles, apf2-01573, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

Federal Street: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF33-005192-M4 (b&w film nitrate neg.)