A Short History

For over a century and a half, the Chicago Police Department has struggled to maintain law and order in a city with a long-standing—if sometimes undeserved—reputation for crime and violence. Although a part-time, non-patrolling system of constables and sheriffs had existed for years, the first full-time, standing police force was organized only in reaction to the explosive tension between German and Irish immigrants and Anglo nativists that erupted in the 1855 Lager Beer Riots. As the city’s population swelled from 30,000 to 300,000 residents between 1850 and 1871, patrolmen tended to maintain order on the beat with the liberal application of their clubs.

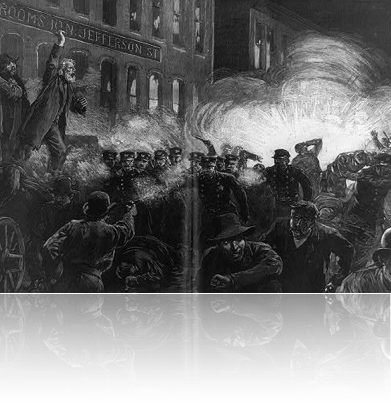

Although the police force—which initially was composed exclusively of native-born Americans—soon employed many foreign-born and especially Irish-American officers, the department became associated with the sometimes-violent repression of the immigrant-led labor movement. Police involvement in the Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Haymarket Affair of 1886 remains a source of controversy to this day. A police intelligence unit, a later incarnation of which would be known as the Red Squad, employed a combination of overt coercion and covert manipulation in its effort to root out labor radicalism.

While officer salaries may have been paid by City Hall, policing in Chicago was a fundamentally local affair controlled by neighborhood politicians working out of ward offices. The police rolls were sources of patronage and, so long as officers fulfilled their political obligations, internal discipline was weak. Many officers supplemented their somewhat meager earnings with small-scale graft. Insofar as a few carefully placed bribes were enough to ensure police protection, vice thrived in a number of geographically bounded districts.

With the coming of prohibition, however, vice became significantly more profitable. Efforts to consolidate control over bootlegging operations provoked the bloody “Beer Wars”—a struggle eventually won by the fabled Al Capone. Provoked by the perceived inability of the police to curb the violence of an increasingly sophisticated criminal element—known in Chicago as the “Outfit”—concerned citizens took matters into their own hands. The Chicago Crime Commission, founded in the same year that the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, monitored law enforcement practices and publicly criticized political interference and corruption in police affairs. The Commission employed the services of a “Secret Six” investigative unit and encouraged Eliot Ness’ 1931 prosecution of Capone on tax-evasion charges.

Despite the activism of the Commission, petty corruption and political patronage continued to plague the department. The 1960 Summerdale Scandal involving a police-burglary ring provoked unprecedented public outcry and pushed a still-young Mayor Richard J. Daley to appoint a reformer, O. W. Wilson, as superintendent of police with the public promise of total political independence. Wilson moved quickly to reorganize the department, removing control over police operations from local political leaders and centralizing power downtown in police headquarters. Under Wilson’s leadership, the department recruited minorities into its ranks and protected civil rights demonstrators in a series of provocative protests even as it attempted to control an uptick in urban rioting and increasingly large—though still not citywide— youth gangs such as the Blackstone Rangers in the South Side neighborhood of Woodlawn.

When Wilson retired in 1967, he left what was probably the most technologically and bureaucratically advanced police force in the country. Despite these advantages, the force would prove unable to meet the challenges that lay ahead. Wilson’s successor, James Conlisk, was unable to control the ghetto riots of 1968. In August 1968, images of Chicago policemen beating demonstrators gathered to protest the Democratic National Convention were broadcast to a national television audience. A special commission created to investigate police conduct at the Convention would dub the incident a “police riot.” The next year, Chicago police officers under the control of State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan shot and killed Chicago Black Panther Party chairman Fred Hampton and member Mark Clark in what was widely believed to be a planned assault. Meanwhile, the Red Squad, originally developed in the aftermath of the Haymarket Affair and implicated in covert police operations in the post-WWI and WWII red scares, stepped up activity throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, collecting information on hundreds of thousands of leftist activists, civil rights leaders and other political dissenters.

The situation, however, was bound to change. In 1973, the Afro-American Patrolmen’s League successfully sued the department to hire more minorities. The next year, a coalition calling itself the Alliance to End Repression challenged the constitutionality of Red Squad activities and eventually won a court order controlling the unit in 1985. Most profoundly, in 1992, the department initiated the Chicago Alternative Policing Strategy (CAPS) in an effort to facilitate interaction and improve relations between Chicagoans and their police force. CAPS promoted interaction between citizens and beat officers and returned a certain measure of non-political control over policing operations to the community.

Further Reading:

Danielle S. Allen, Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004)

William J. Bopp, “O. W.”: O. W. Wilson and the Search for a Police Profession (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1997)

Frank J. Donner, Protectors of Privilege: Red Squads and Police Repression in Urban America (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1990)

Encyclopedia of Chicago, James Grossman, Ann Durkin Keating and Janice L. Reiff, eds. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004)

David R. Farber, Chicago ’68 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985)

Richard C. Lindberg, To Serve and Collect: Chicago Politics and Police Corruption from the Lager Beer Riot to the Summerdale Scandal (New York: Praeger, 1991)

Wesley G. Skogan and Susan M. Hartnett, Community Policing, Chicago Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997)

Learn More

Image sources

Haymarket woodcut: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-796 (b&w film copy neg.)

Police officer: Chicago History Musuem. Chicago Daily News negatives collection, DN-0084682. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

Police

uchicago®  ©2007 The University of Chicago®

©2007 The University of Chicago®  5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637

5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637  773-702-1234

773-702-1234

©2007 The University of Chicago®

©2007 The University of Chicago®  5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637

5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637  773-702-1234

773-702-1234