A Short History

As the training grounds of the young, Chicago’s schools have perpetually been sites of conflict and controversy. Their complex history offers a glimpse at the hopes and fears of diverse Chicagoans as they struggled to provide for the future of their children and their city.

In the middle decades of the 19th century, Chicago developed a modern and expanding public school system hurrying to keep up with increasing needs of a rapidly growing industrial city—sometimes with questionable success. Alongside the public system, a network of Catholic and private schools developed to help meet the needs of an ethnically and linguistically diverse population. Prior to the particularly xenophobic outbursts of the WWI period and its aftermath, a politically powerful bloc of ethnic Germans led efforts to provide non-English curricula in Chicago schools despite strong nativist opposition.

Led by John Dewey, Francis Parker and Jane Addams, turn-of-the-century Chicago emerged as a center of progressive educational thought. Dewey’s Lab School at the University of Chicago, Parker’s Practice School and Addams’ Hull House tested new progressive theories and practices that aimed at breaking with the traditional model of educational regimentation and replacing it with a more democratic and experiential curriculum. A group of businessmen who also called themselves progressives sought to remodel Chicago’s schools to train students for industrial employment. Though some objected that this system would harden socioeconomic differences, these business-oriented reformers established a vocational system that taught both relevant job skills and desirable attitudes toward work and discipline.

Meanwhile, educational standards dropped off sharply in Chicago schools during the interwar period. Elected officials had long considered the public school system a source of patronage and with the sudden arrival of the Great Depression clout-heavy janitors and secretaries kept their jobs while teachers—and, by extension, their students—found themselves out in the cold. Enrollment in parochial schools climbed, eventually peaking in the 1950s. The city sought to reverse this trend by appointing a series of independent and strong willed superintendents—most notably Benjamin Willis in 1953, a man who considered the schools “his own principality.” His firmness, however, came at a cost.

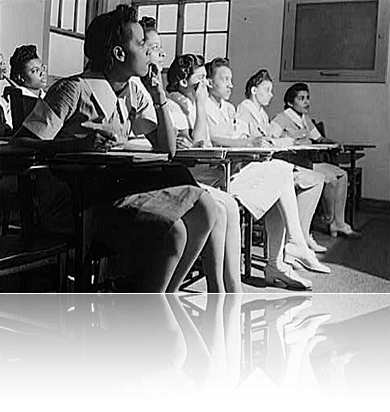

Willis energized a moribund system over the first decade of his tenure. But even as he rebuilt the physical plant of Chicago’s schools and brought in fresh enrollments, a storm was gathering in the overcrowded, segregated and neglected schools of the Black Belt. Unlike the South, school segregation in the North was propped up not by explicit legal regulation but by a traditional commitment to neighborhood schooling combined with racially motivated determinations of school catchments. The city’s residential segregation was reflected in the “natural” segregation of its schools. But as Chicago’s growing black community was forced into ever-more crowded and dilapidated schools, Willis refused to transfer black students to nearby white schools with empty classrooms and modern facilities. Instead, he shortened the school day for black students, instituted double shifts and installed temporary classroom trailers that fast became known as “Willis Wagons.” The convenient myth of “natural” school segregation was coming apart—and Willis’ once lauded firmness was fast becoming a liability.

Over the 1963-64 school year, the anger and frustration in the black community erupted in a series of well-organized marches, pickets and one-day school boycotts aimed at pressuring Willis to change these segregationist polices. Led by the Temporary Woodlawn Organization and the Congress of Racial Equality and armed with carefully researched reports written by local intellectuals, the protesters exposed the vast inequities of the public school system. Caught between the competing demands of black and white voters Mayor Richard J. Daley was only too happy to maintain the political independence of his embattled superintendent.

In 1966, Willis retired from office and was replaced by a man with an integrationist record. Unfortunately, regime change alone was incapable of desegregating Chicago’s public schools. As the Black Belt expanded outward block-by-block, local schools “transitioned” nearly as fast as the neighborhoods they were located in. Increasingly, white families sent their children to private and parochial schools, enrolled them in still-segregated vocational programs or left for suburban school districts. With Milliken v. Bradley in 1974, the Supreme Court denied the constitutional necessity of metropolitan desegregation plans and legally safeguarded the suburban haven of these white families.

Even as suburban districts prospered by this migration of families and tax-dollars, the process of “white-flight” undermined the city’s fiscal base. By 1980, the rapid loss put the Chicago public system in the red and the Illinois School Finance Authority was forced to assume management of the city’s schools. Seven years later, U.S. Secretary of Education William Bennett went on record calling Chicago’s school system “the worst in the nation.”

Since then, major reforms—including Mayor Harold Washington’s 1988 implementation of limited parent control over public schools, Mayor Richard M. Daley’s 1995 corporate restructuring of the system and the charter school and small school movements—have significantly improved educational quality. But the achievement of Chicago Public School students still lags behind that of their suburban peers and the goal of genuine integration remains elusive.

Further Reading:

Encyclopedia of Chicago, James Grossman, Ann Durkin Keating and Janice L. Reiff, eds. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004)

Mary J. Herrick, The Chicago Schools: A Social and Political History (Beverley Hills, CA: Sage, 1971)

James W. Sanders, Education of an Urban Minority: Catholics in Chicago, 1833-1965 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977)

Education

Learn More

uchicago®  ©2007 The University of Chicago®

©2007 The University of Chicago®  5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637

5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637  773-702-1234

773-702-1234

©2007 The University of Chicago®

©2007 The University of Chicago®  5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637

5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637  773-702-1234

773-702-1234

Image sources

Graduating Class: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF34-038793-D (b&w film neg.)

Listening Class: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USW3-000314-D (b&w film neg.)